When Does Finn Find Out the Baby Is Not His

2nd (1st Usa) edition book cover | |

| Author | Mark Twain |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | E. Due west. Kemble |

| State | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Tom Sawyer |

| Genre | Picaresque novel |

| Publisher | Chatto & Windus / Charles L. Webster And Company. |

| Publication date | Dec 10, 1884 (UK and Canada) 1885[1] (Usa) |

| Pages | 366 |

| OCLC | 29489461 |

| Preceded by | The Adventures of Tom Sawyer |

| Followed by | Tom Sawyer Away |

| Text | Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at Wikisource |

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or as it is known in more recent editions, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn , is a novel by American author Mark Twain, which was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the U.s. in February 1885.

Unremarkably named amid the Great American Novels, the work is among the showtime in major American literature to be written throughout in vernacular English language, characterized by local color regionalism. It is told in the first person by Huckleberry "Huck" Finn, the narrator of two other Twain novels (Tom Sawyer Abroad and Tom Sawyer, Detective) and a friend of Tom Sawyer. It is a directly sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

The book is noted for "irresolute the course of children's literature" in the United States for the "deeply felt portrayal of boyhood".[2] It is besides known for its colorful clarification of people and places along the Mississippi River. Set in a Southern antebellum lodge that had ceased to be over xx years earlier the work was published, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is an oft scathing satire on entrenched attitudes, particularly racism.

Perennially popular with readers, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has likewise been the connected object of study by literary critics since its publication. The book was widely criticized upon release because of its extensive apply of fibroid language. Throughout the 20th century, and despite arguments that the protagonist and the tenor of the book are anti-racist,[3] [four] criticism of the book continued due to both its perceived apply of racial stereotypes and its frequent apply of the racial slur "nigger".

Characters [edit]

In order of appearance:

- Tom Sawyer is Huck'south best friend and peer, the main character of other Twain novels and the leader of the town boys in adventures. He is mischievous, skillful hearted, and "the best fighter and the smartest kid in town".[5]

- Blueberry Finn, "Huck" to his friends, is a boy about "13 or fourteen or along there" years old. (Chapter 17) He has been brought up past his male parent, the town drunk, and has a difficult time fitting into society. In the novel, Huck's good nature offers a contrast to the inadequacies and inequalities in lodge.

- Widow Douglas is the kind woman who takes Huck in after he helped save her from a fierce dwelling invasion. She tries her all-time to civilize Huck, believing information technology is her Christian duty.

- Miss Watson is the widow's sister, a tough one-time spinster who also lives with them. She is adequately hard on Huck, causing him to resent her a good deal. Mark Twain may have fatigued inspiration for this character from several people he knew in his life.[5]

- Jim is Miss Watson's physically large but mild-mannered slave. Huck becomes very close to Jim when they reunite afterwards Jim flees Miss Watson's household to seek refuge from slavery, and Huck and Jim go fellow travelers on the Mississippi River.

- "Pap" Finn, Huck'due south father, a brutal alcoholic drifter. He resents Huck getting any kind of teaching. His just genuine interest in his son involves begging or extorting coin to feed his alcohol addiction.

- Judith Loftus plays a small function in the novel — being the kind and perceptive woman whom Huck talks to in society to find out virtually the search for Jim — simply many critics believe her to be the all-time fatigued female character in the novel.[5]

- The Grangerfords, an aristocratic Kentuckian family headed past the sexagenarian Colonel Saul Grangerford, take Huck in after he is separated from Jim on the Mississippi. Huck becomes close friends with the youngest male person of the family, Buck Grangerford, who is Huck's age. By the time Huck meets them, the Grangerfords accept been engaged in an age-quondam blood feud with some other local family, the Shepherdsons.

- The Knuckles and the King are two otherwise unnamed con artists whom Huck and Jim take aboard their raft just before the first of their Arkansas adventures. They pose equally the long-lost Duke of Bridgewater and the long-expressionless Louis XVII of French republic in an attempt to over-awe Huck and Jim, who quickly come up to recognize them for what they are, but cynically pretend to have their claims to avert disharmonize.

- Md Robinson is the only human being who recognizes that the Male monarch and Knuckles are phonies when they pretend to be British. He warns the townspeople, only they ignore him.

- Mary Jane, Joanna, and Susan Wilks are the three young nieces of their wealthy guardian, Peter Wilks, who has recently died. The Duke and the King try to steal their inheritance by posing as Peter's estranged brothers from England.

- Aunt Sally and Uncle Silas Phelps buy Jim from the Knuckles and the King. She is a loving, high-strung "farmer'south wife", and he a plodding erstwhile human, both a farmer and a preacher. Huck poses equally their nephew Tom Sawyer after he parts from the conmen.

Plot summary [edit]

Huckleberry Finn, as depicted by East. West. Kemble in the original 1884 edition of the book

In Missouri [edit]

The story begins in fictional St. petersburg, Missouri (based on the bodily town of Hannibal, Missouri), on the shore of the Mississippi River "40 to 50 years agone" (the novel having been published in 1884). Blueberry "Huck" Finn (the protagonist and start-person narrator) and his friend, Thomas "Tom" Sawyer, have each come into a considerable sum of coin as a effect of their before adventures (detailed in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer). Huck explains how he is placed under the guardianship of the Widow Douglas, who, together with her stringent sister, Miss Watson, are attempting to "sivilize" him and teach him religion. Huck finds civilized life confining. His spirits are raised when Tom Sawyer helps him to slip past Miss Watson's slave, Jim, so he tin meet upward with Tom's gang of self-proclaimed "robbers". Just as the gang'due south activities begin to bore Huck, his shiftless father, "Pap", an abusive alcoholic, of a sudden reappears. Huck, who knows his father volition spend the coin on alcohol, is successful at keeping his fortune out of his father's hands. Pap, notwithstanding, kidnaps Huck and takes him out of boondocks.

In Illinois, Jackson'due south Island and while going Downriver [edit]

Pap forcibly moves Huck to an abandoned motel in the woods along the Illinois shoreline. To evade further violence and escape imprisonment, Huck elaborately fakes his own murder, steals his begetter's provisions, and sets off downriver in a 13/14-foot long canoe he finds drifting downstream. Soon, he settles comfortably on Jackson's Isle, where he reunites with Jim, Miss Watson's slave. Jim has also run away later he overheard Miss Watson planning to sell him "down the river" to presumably more brutal owners. Jim plans to make his way to the town of Cairo in Illinois, a free state, so that he can later purchase the rest of his enslaved family unit's freedom. At first, Huck is conflicted almost the sin and crime of supporting a runaway slave, but as the two talk in-depth and bond over their mutually held superstitions, Huck emotionally connects with Jim, who increasingly becomes Huck'south close friend and guardian. After heavy flooding on the river, the two detect a raft (which they keep) besides as an entire firm floating on the river (Chapter 9: "The Business firm of Death Floats By"). Entering the house to seek loot, Jim finds the naked body of a dead man lying on the flooring, shot in the back. He prevents Huck from viewing the corpse.[6]

To notice out the latest news in town, Huck dresses every bit a girl and enters the firm of Judith Loftus, a woman new to the area. Huck learns from her about the news of his own supposed murder; Pap was initially blamed, only since Jim ran away he is as well a suspect and a reward of 300 dollars for Jim'due south capture has initiated a manhunt. Mrs. Loftus becomes increasingly suspicious that Huck is a boy, finally proving it by a series of tests. Huck develops another story on the wing and explains his disguise as the simply way to escape from an abusive foster family unit. In one case he is exposed, she nevertheless allows him to leave her home without commotion, not realizing that he is the allegedly murdered boy they have just been discussing. Huck returns to Jim to tell him the news and that a search party is coming to Jackson's Island that very night. The ii hastily load up the raft and depart.

Subsequently a while, Huck and Jim encounter a grounded steamer. Searching information technology, they stumble upon two thieves named Neb and Jake Packard discussing murdering a third named Jim Turner, but they flee earlier being noticed in the thieves' gunkhole as their raft has drifted abroad. They detect their own raft once again and go on the thieves' loot and sink the thieves' boat. Huck tricks a watchman on a steamer into going to rescue the thieves stranded on the wreck to assuage his conscience. They are later separated in a fog, making Jim (on the raft) intensely anxious, and when they reunite, Huck tricks Jim into thinking he dreamed the entire incident. Jim is not deceived for long and is deeply hurt that his friend should have teased him so mercilessly. Huck becomes remorseful and apologizes to Jim, though his conscience troubles him nearly humbling himself to a Blackness man.

In Kentucky: the Grangerfords and Shepherdsons [edit]

Traveling onward, Huck and Jim'due south raft is struck past a passing steamship, once again separating the two. Huck is given shelter on the Kentucky side of the river by the Grangerfords, an "aristocratic" family. He befriends Buck Grangerford, a boy most his age, and learns that the Grangerfords are engaged in a 30-twelvemonth claret feud confronting another family, the Shepherdsons. Although Huck asks Buck why the feud started in the first place, he is told no 1 knows anymore. The Grangerfords and Shepherdsons go to the aforementioned church, which ironically preaches brotherly dearest. The vendetta finally comes to a caput when Buck'south older sister elopes with a member of the Shepherdson clan. In the resulting disharmonize, all the Grangerford males from this branch of the family are shot and killed by the remaining Shepherdsons — including Buck, whose horrific murder Huck witnesses. He is immensely relieved to be reunited with Jim, who has since recovered and repaired the raft.

In Arkansas: the Duke and the Rex [edit]

Virtually the Arkansas-Missouri-Tennessee border, Jim and Huck take two on-the-run grifters aboard the raft. The younger man, who is about thirty, introduces himself as the long-lost son of an English language duke (the Duke of Bridgewater). The older one, about 70, and then trumps this outrageous claim by alleging that he himself is the Lost Dauphin, the son of Louis 16 and rightful King of French republic. The "knuckles" and "king" soon go permanent passengers on Jim and Huck's raft, committing a series of conviction schemes upon unsuspecting locals all along their journey. To divert public suspicion from Jim, they pretend he is a runaway slave who has been recaptured, but later paint him blue and telephone call him the "Sick Arab" and then that he can motility virtually the raft without bindings.

On i occasion, the swindlers advertise a three-night engagement of a play called "The Majestic Nonesuch". The play turns out to be simply a couple of minutes' worth of an absurd, bawdy sham. On the afternoon of the showtime functioning, a boozer chosen Boggs is shot dead by a gentleman named Colonel Sherburn; a lynch mob forms to retaliate confronting Sherburn; and Sherburn, surrounded at his abode, disperses the mob by making a defiant speech describing how true lynching should be done. By the 3rd night of "The Royal Nonesuch", the townspeople prepare for their revenge on the duke and king for their money-making scam, simply the two cleverly skip town together with Huck and Jim but earlier the performance begins.

In the next town, the ii swindlers and so impersonate brothers of Peter Wilks, a recently deceased human of property. To match accounts of Wilks'southward brothers, the king attempts an English accent and the duke pretends to be a deafened-mute while starting to collect Wilks's inheritance. Huck decides that Wilks's three orphaned nieces, who treat Huck with kindness, do non deserve to exist cheated thus and so he tries to retrieve for them the stolen inheritance. In a desperate moment, Huck is forced to hide the money in Wilks'south coffin, which is abruptly buried the next morning time. The arrival of two new men who seem to be the real brothers throws everything into confusion, so that the townspeople decide to dig up the coffin in gild to determine which are the true brothers, merely, with everyone else distracted, Huck leaves for the raft, hoping to never see the knuckles and male monarch once more. All of a sudden, though, the 2 villains return, much to Huck's despair. When Huck is finally able to get abroad a second fourth dimension, he finds to his horror that the swindlers have sold Jim abroad to a family that intends to render him to his proper possessor for the advantage. Defying his censor and accepting the negative religious consequences he expects for his actions—"All correct, then, I'll go to hell!"—Huck resolves to free Jim one time and for all.

On the Phelpses' farm [edit]

Huck learns that Jim is being held at the plantation of Silas and Sally Phelps. The family's nephew, Tom, is expected for a visit at the same time equally Huck's arrival, so Huck is mistaken for Tom and welcomed into their dwelling house. He plays forth, hoping to find Jim's location and gratis him; in a surprising plot twist, it is revealed that the expected nephew is, in fact, Tom Sawyer. When Huck intercepts the real Tom Sawyer on the road and tells him everything, Tom decides to join Huck's scheme, pretending to be his own younger half-brother, Sid, while Huck continues pretending to exist Tom. In the concurrently, Jim has told the family virtually the two grifters and the new plan for "The Royal Nonesuch", and then the townspeople capture the duke and rex, who are then tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a rails.

Rather than simply sneaking Jim out of the shed where he is existence held, Tom develops an elaborate plan to free him, involving hugger-mugger messages, a hidden tunnel, snakes in a shed, a rope ladder sent in Jim'due south food, and other elements from adventure books he has read,[vii] including an bearding notation to the Phelps warning them of the whole scheme. During the actual escape and resulting pursuit, Tom is shot in the leg, while Jim remains past his side, risking recapture rather than completing his escape solitary. Although a local doc admires Jim's decency, he has Jim arrested in his sleep and returned to the Phelpses. Afterwards this, events apace resolve themselves. Tom's Aunt Polly arrives and reveals Huck and Tom's true identities to the Phelps family. Jim is revealed to be a free human: Miss Watson died two months before and freed Jim in her volition, only Tom (who already knew this) chose not to reveal this information to Huck then that he could come up with an artful rescue plan for Jim. Jim tells Huck that Huck's father (Pap Finn) has been dead for some time (he was the dead man they constitute earlier in the floating firm), and and then Huck may now return safely to Leningrad. Huck declares that he is quite glad to exist done writing his story, and despite Sally's plans to adopt and civilize him, he intends to abscond west to Indian Territory.

Theme [edit]

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn explores themes of race and identity. A complexity exists concerning Jim's character. While some scholars point out that Jim is expert-hearted and moral, and he is not unintelligent (in contrast to several of the more than negatively depicted white characters), others have criticized the novel as racist, citing the use of the word "nigger" and emphasizing the stereotypically "comic" treatment of Jim's lack of pedagogy, superstition and ignorance.[viii] [nine]

Throughout the story, Huck is in moral conflict with the received values of the society in which he lives. Huck is unable consciously to rebut those values even in his thoughts but he makes a moral choice based on his ain valuation of Jim's friendship and human worth, a conclusion in direct opposition to the things he has been taught. Twain, in his lecture notes, proposes that "a sound eye is a surer guide than an sick-trained conscience" and goes on to describe the novel every bit "...a volume of mine where a sound center and a deformed conscience come into collision and conscience suffers defeat".[10]

To highlight the hypocrisy required to condone slavery within an ostensibly moral system, Twain has Huck'southward male parent enslave his son, isolate him and beat him. When Huck escapes, he immediately encounters Jim "illegally" doing the same affair. The treatments both of them receive are radically different, peculiarly in an run across with Mrs. Judith Loftus who takes pity on who she presumes to be a runaway apprentice, Huck, even so boasts about her husband sending the hounds later a runaway slave, Jim.[xi]

Some scholars discuss Huck's own graphic symbol, and the novel itself, in the context of its relation to African-American civilisation as a whole. John Alberti quotes Shelley Fisher Fishkin, who writes in her 1990s volume Was Huck Black?: Mark Twain and African-American Voices, "past limiting their field of inquiry to the periphery," white scholars "accept missed the means in which African-American voices shaped Twain'southward creative imagination at its core." It is suggested that the character of Blueberry Finn illustrates the correlation, and even interrelatedness, between white and Black culture in the United States.[12]

Illustrations [edit]

The original illustrations were done by Due east.W. Kemble, at the fourth dimension a immature artist working for Life magazine. Kemble was hand-picked past Twain, who admired his work. Hearn suggests that Twain and Kemble had a similar skill, writing that:

Any he may accept lacked in technical grace ... Kemble shared with the greatest illustrators the ability to give even the minor private in a text his own distinct visual personality; just as Twain so deftly defined a full-rounded character in a few phrases, so also did Kemble draw with a few strokes of his pen that same unabridged personage.[13]

As Kemble could afford only one model, about of his illustrations produced for the book were done by guesswork. When the novel was published, the illustrations were praised even as the novel was harshly criticized. Due east.Westward. Kemble produced some other ready of illustrations for Harper's and the American Publishing Company in 1898 and 1899 subsequently Twain lost the copyright.[fourteen]

Publication's effect on literary climate [edit]

Twain initially conceived of the piece of work equally a sequel to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer that would follow Huckleberry Finn through adulthood. Get-go with a few pages he had removed from the before novel, Twain began work on a manuscript he originally titled Blueberry Finn'south Autobiography. Twain worked on the manuscript off and on for the next several years, ultimately abandoning his original program of following Huck's development into machismo. He appeared to have lost interest in the manuscript while information technology was in progress, and prepare it aside for several years. After making a trip downwards the Hudson River, Twain returned to his piece of work on the novel. Upon completion, the novel'south title closely paralleled its predecessor's: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade).[15]

Mark Twain composed the story in pen on notepaper between 1876 and 1883. Paul Needham, who supervised the authentication of the manuscript for Sotheby's books and manuscripts department in New York in 1991, stated, "What you meet is [Clemens'] attempt to motility abroad from pure literary writing to dialect writing". For example, Twain revised the opening line of Huck Finn three times. He initially wrote, "You will not know about me", which he changed to, "You practise not know near me", before settling on the final version, "You don't know about me, without you have read a book past the proper noun of 'The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'; just that ain't no affair."[16] The revisions besides testify how Twain reworked his material to strengthen the characters of Huck and Jim, as well as his sensitivity to the then-current debate over literacy and voting.[17] [18]

A later version was the kickoff typewritten manuscript delivered to a printer.[xix]

Demand for the book spread exterior of the United States. Adventures of Blueberry Finn was eventually published on December 10, 1884, in Canada and the Great britain, and on February 18, 1885, in the U.s.a..[20] The illustration on page 283 became a betoken of issue after an engraver, whose identity was never discovered, made a last-minute addition to the printing plate of Kemble's film of erstwhile Silas Phelps, which drew attending to Phelps' groin. Xxx m copies of the book had been printed earlier the obscenity was discovered. A new plate was made to right the illustration and repair the existing copies.[21] [22]

In 1885, the Buffalo Public Library's curator, James Fraser Gluck, approached Twain to donate the manuscript to the library. Twain did and so. After information technology was believed that half of the pages had been misplaced by the printer. In 1991, the missing starting time half turned upwards in a steamer trunk owned by descendants of Gluck'southward. The library successfully claimed possession and, in 1994, opened the Mark Twain Room to showcase the treasure.[23]

In relation to the literary climate at the time of the book'due south publication in 1885, Henry Nash Smith describes the importance of Mark Twain's already established reputation as a "professional person humorist", having already published over a dozen other works. Smith suggests that while the "dismantling of the corrupt Romanticism of the later nineteenth century was a necessary performance," Adventures of Huckleberry Finn illustrated "previously inaccessible resources of imaginative power, simply also made vernacular language, with its new sources of pleasure and new energy, available for American prose and poetry in the twentieth century."[24]

Disquisitional reception and banning [edit]

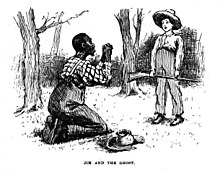

In this scene illustrated past E. W. Kemble, Jim has given Huck upward for dead and when he reappears thinks he must be a ghost.

While it is clear that Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was controversial from the offset, Norman Mailer, writing in The New York Times in 1984, concluded that Twain's novel was not initially "also unpleasantly regarded." In fact, Mailer writes: "the disquisitional climate could hardly anticipate T. Southward. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway'due south encomiums 50 years later on," reviews that would remain longstanding in the American consciousness.[25]

Alberti suggests that the academic establishment responded to the book'southward challenges both dismissively and with confusion. During Twain's time and today, defenders of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn "lump all nonacademic critics of the volume together as extremists and 'censors', thus equating the complaints about the book's 'coarseness' from the genteel bourgeois trustees of the Concord Public Library in the 1880s with more contempo objections based on race and civil rights."[12]

Upon outcome of the American edition in 1885, several libraries banned it from their shelves.[26] The early on criticism focused on what was perceived as the book's crudeness. I incident was recounted in the newspaper the Boston Transcript:

The Concur (Mass.) Public Library committee has decided to exclude Mark Twain's latest volume from the library. Ane member of the committee says that, while he does not wish to call information technology immoral, he thinks information technology contains only niggling sense of humour, and that of a very coarse blazon. He regards it as the veriest trash. The library and the other members of the committee entertain similar views, characterizing it as rough, coarse, and inelegant, dealing with a series of experiences not elevating, the whole book being more suited to the slums than to intelligent, respectable people.[27]

Writer Louisa May Alcott criticized the book's publication likewise, maxim that if Twain "[could not] recollect of something better to tell our pure-minded lads and lasses he had best stop writing for them".[28] [29]

Twain later remarked to his editor, "Apparently, the Concord library has condemned Huck as 'trash and only suitable for the slums.' This will sell the states another twenty-5 thousand copies for certain!"

In 1905, New York'due south Brooklyn Public Library also banned the book due to "bad word choice" and Huck'south having "non only itched simply scratched" within the novel, which was considered obscene. When asked past a Brooklyn librarian nigh the state of affairs, Twain sardonically replied:

I am profoundly troubled past what y'all say. I wrote 'Tom Sawyer' & 'Huck Finn' for adults exclusively, & it ever distressed me when I find that boys and girls accept been allowed admission to them. The mind that becomes soiled in youth can never again be washed clean. I know this by my ain experience, & to this twenty-four hour period I cherish an unappeased bitterness confronting the unfaithful guardians of my young life, who non just permitted merely compelled me to read an unexpurgated Bible through earlier I was 15 years erstwhile. None can do that and ever draw a clean sugariness breath once again on this side of the grave.[30]

Many subsequent critics, Ernest Hemingway among them, take deprecated the final chapters, claiming the book "devolves into piffling more minstrel-show satire and broad comedy" later Jim is detained.[31] Although Hemingway declared, "All modern American literature comes from" Huck Finn, and hailed it equally "the best book we've had", he cautioned, "If you must read it you must finish where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys [sic]. That is the real finish. The residuum is simply cheating."[32] [33] The African-American writer Ralph Ellison argued that "Hemingway missed completely the structural, symbolic and moral necessity for that part of the plot in which the boys rescue Jim. Nevertheless it is precisely this role which gives the novel its significance."[34] Pulitzer Prize winner Ron Powers states in his Twain biography (Marking Twain: A Life) that "Blueberry Finn endures equally a consensus masterpiece despite these final capacity", in which Tom Sawyer leads Huck through elaborate machinations to rescue Jim.[35]

Controversy [edit]

In his introduction to The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, Michael Patrick Hearn writes that Twain "could exist uninhibitedly vulgar", and quotes critic William Dean Howells, a Twain gimmicky, who wrote that the author'southward "humour was not for most women". However, Hearn continues past explaining that "the reticent Howells found nothing in the proofs of Huckleberry Finn so offensive that it needed to be struck out".[36]

Much of modern scholarship of Huckleberry Finn has focused on its treatment of race. Many Twain scholars have argued that the book, by humanizing Jim and exposing the fallacies of the racist assumptions of slavery, is an attack on racism.[37] Others have argued that the volume falls short on this score, especially in its depiction of Jim.[26] According to Professor Stephen Railton of the University of Virginia, Twain was unable to fully ascension to a higher place the stereotypes of Black people that white readers of his era expected and enjoyed, and, therefore, resorted to minstrel show-style one-act to provide humor at Jim'southward expense, and ended up confirming rather than challenging belatedly-19th century racist stereotypes.[38]

In ane instance, the controversy caused a drastically contradistinct interpretation of the text: in 1955, CBS tried to avoid controversial material in a televised version of the book, by deleting all mention of slavery and omitting the character of Jim entirely.[39]

Because of this controversy over whether Huckleberry Finn is racist or anti-racist, and because the discussion "nigger" is frequently used in the novel (a commonly used word in Twain's time that has since become vulgar and taboo), many accept questioned the appropriateness of pedagogy the volume in the U.Due south. public school system—this questioning of the word "nigger" is illustrated by a school administrator of Virginia in 1982 calling the novel the "almost grotesque instance of racism I've ever seen in my life".[40] According to the American Library Association, Huckleberry Finn was the fifth most frequently challenged volume in the United States during the 1990s.[41]

There have been several more recent cases involving protests for the banning of the novel. In 2003, high school student Calista Phair and her grandmother, Beatrice Clark, in Renton, Washington, proposed banning the volume from classroom learning in the Renton School District, though non from whatever public libraries, because of the word "nigger". The ii curriculum committees that considered her asking somewhen decided to proceed the novel on the 11th grade curriculum, though they suspended it until a panel had time to review the novel and set up a specific pedagogy procedure for the novel's controversial topics.[42]

In 2009, a Washington state high school teacher, John Foley, chosen for replacing Adventures of Blueberry Finn with a more mod novel.[43] In an opinion column that Foley wrote in the Seattle Post Intelligencer, he states that all "novels that use the 'N-word' repeatedly need to get." He states that teaching the novel is non just unnecessary, simply difficult due to the offensive language within the novel with many students becoming uncomfortable at "just hear[ing] the Northward-word."[44]

In 2016, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was removed from a public schoolhouse commune in Virginia, along with the novel To Kill a Mockingbird, due to their use of racial slurs.[45] [46]

Expurgated editions [edit]

Publishers have fabricated their own attempts at easing the controversy by mode of releasing editions of the book with the give-and-take "nigger" replaced past less controversial words. A 2011 edition of the book, published by NewSouth Books, employed the word "slave" (although the give-and-take is not properly applied to a freed homo). Their argument for making the modify was to offering the reader a choice of reading a "sanitized" version if they were non comfortable with the original.[47] Marker Twain scholar Alan Gribben said he hoped the edition would be more friendly for utilize in classrooms, rather than accept the work banned outright from classroom reading lists due to its language.[48]

According to publisher Suzanne La Rosa, "At NewSouth, nosotros saw the value in an edition that would help the works find new readers. If the publication sparks good debate about how language impacts learning or nearly the nature of censorship or the fashion in which racial slurs exercise their baneful influence, then our mission in publishing this new edition of Twain's works will be more than emphatically fulfilled."[49] Some other scholar, Thomas Wortham, criticized the changes, saying the new edition "doesn't challenge children to ask, 'Why would a child like Huck apply such reprehensible language?'"[50]

Adaptations [edit]

Picture show [edit]

- Huck and Tom (1918 silent) past Famous Players-Lasky; directed by William Desmond Taylor; starring Jack Pickford as Tom, Robert Gordon as Huck and Clara Horton as Becky[51]

- Huckleberry Finn (1920 silent) past Famous Players-Lasky; directed by William Desmond Taylor; starring Lewis Sargent as Huck, Gordon Griffith as Tom and Thelma Salter as Becky[52] [53]

- Huckleberry Finn (1931) by Paramount Pictures; directed by Norman Taurog; starring Jackie Coogan as Tom, Junior Durkin equally Huck, and Mitzi Dark-green equally Becky[53] [54]

- The Adventures of Blueberry Finn (1939) by MGM; directed by Richard Thorpe; starring Mickey Rooney as Huck[55]

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1955), starring Thomas Mitchell and John Carradine[56]

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960), directed past Michael Curtiz, starring Eddie Hodges and Archie Moore[57]

- Hopelessly Lost (1973), a Soviet pic[58]

- Huckleberry Finn (1974), a musical moving-picture show[59]

- Huckleberry Finn (1975), an ABC movie of the calendar week with Ron Howard as Huck Finn[60]

- The Adventures of Con Sawyer and Hucklemary Finn (1985), an ABC movie of the week with Drew Barrymore every bit Con Sawyer[61]

- The Adventures of Huck Finn (1993), starring Elijah Forest and Courtney B. Vance[62]

- Tom and Huck (1995), starring Jonathan Taylor Thomas as Tom and Brad Renfro as Huck[63]

- Tomato Sawyer and Huckleberry Larry's Large River Rescue (2008), a VeggieTales parody[64]

- The Adventures of Huck Finn (2012), a German film starring Leon Seidel and directed past Hermine Huntgeburth[65]

- Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn (2014), starring Joel Courtney as Tom Sawyer, Jake T. Austin as Huckleberry Finn, Katherine McNamara as Becky Thatcher[66]

Television [edit]

- Huckleberry no Bōken, a 1976 Japanese anime with 26 episodes[67]

- Blueberry Finn and His Friends, a 1979 series starring Ian Tracey[68]

- Adventures of Blueberry Finn, a 1985 PBS TV adaptation directed by Peter H. Hunt, starring Patrick Day and Samm-Art Williams.

- Huckleberry Finn Monogatari (ハックルベリー・フィン物語), a 1994 Japanese anime with 26 episodes, produced by NHK[69]

Other [edit]

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1973), by Robert James Dixson – a simplified version[lxx]

- Large River: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1985 Broadway musical with lyrics and music by Roger Miller[71]

- Manga Classics: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn published by UDON Amusement's Manga Classics imprint was released in November 2017.[72]

[edit]

Literature [edit]

- Finn: A Novel (2007), by Jon Clinch – a novel about Huck's begetter, Pap Finn (ISBN 0812977149)

- Huck Out W (2017), by Robert Coover – continues Huck's and Tom's adventures during the 1860s and 1870s (ISBN 0393608441)

- The Further Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1983) past Greg Matthews – continues Huck's and Jim's adventures as they "calorie-free out for the territory" and wind up in the throes of the California Gold Rush of 1849[73] [74] [75] [76]

- My Jim (2005), by Nancy Rawles – a novel narrated largely by Sadie, Jim's enslaved wife (ISBN 140005401X)

Music [edit]

- Mississippi Suite (1926), past Ferde Grofe: the 2nd movement is a lighthearted whimsical piece entitled "Huckleberry Finn"[77]

- Blueberry Finn EP (2009), comprising v songs from Kurt Weill'due south unfinished musical, by Duke Special[78]

Television [edit]

- The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a 1968 children'south serial produced by Hanna-Barbera combining alive-action and blitheness[79]

See too [edit]

- Mark Twain bibliography

- List of films featuring slavery

- The Story of a Bad Boy

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's comrade)…. 1885.

- ^ "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn | Summary & Characters". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Twain, Mark (October 1885). Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer'southward comrade).... ... - Full View – HathiTrust Digital Library – HathiTrust Digital Library. HathiTrust.

- ^ Jacob O'Leary, "Critical Annotation of "Minstrel Shackles and Nineteenth Century 'Liberality' in Huckleberry Finn" (Fredrick Woodard and Donnarae MacCann)," Wiki Service, University of Iowa, last modified February eleven, 2012, accessed April 12, 2012 Archived March 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Hill, Richard (2002). Mark Twain Amongst The Scholars: Reconsidering Gimmicky Twain Criticism. SJK Publishing Industries, Inc. pp. 67–90. ISBN978-0-87875-527-ane.

- ^ Ira Fistell (2012). Ira Fistell's Mark Twain: Three Encounters. Xlibris. ISBN 9781469178721 p. 94. "Huck and Jim's showtime adventure together—the Firm of Decease incident which occupies Chapter ix. This sequence seems to me to be quite important both to the technical functioning of the plot and to the larger pregnant of the novel. The House of Death is a two-story frame building that comes floating downstream, i paragraph afterwards Huck and Jim catch their presently—to—exist famous raft. While Twain never explicitly says so, his description of the business firm and its contents ..."

- ^ Victor A. Doyno (1991). Writing Huck Finn: Marker Twain'due south creative procedure. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 191. ISBN9780812214482.

- ^ 2. Jacob O'Leary, "Critical Annotation of "Minstrel Shackles and Nineteenth Century 'Liberality' in Huckleberry Finn" (Fredrick Woodard and Donnarae MacCann)," Wiki Service, University of Iowa, terminal modified February 11, 2012, accessed Apr 12, 2012 Archived March 12, 2011, at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ Fredrick Woodard and Donnarae MacCann, "Minstrel Shackles and Nineteenth Century "Liberality" in Huckleberry Finn," in Satire or evasion?: Black perspectives on Huckleberry Finn, eds. James S. Leonard, Thomas A. Tenney, and Thadious K. Davis (Durham, NC: Knuckles University Press, 1992).

- ^ Mark Twain (1895). Notebook No. 35. Typescript, P. 35. Mark Twain Papers. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Foley, Barbara (1995). "Reviewed work: Satire or Evasion? Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn, James S. Leonard, Thomas A. Tenney, Thadious Davis; the Word in Black and White: Reading "Race" in American Literature, 1638-1867, Dana D. Nelson". Modernistic Philology. 92 (iii): 379–385. doi:10.1086/392258. JSTOR 438790.

- ^ a b Alberti, John (1995). "The Nigger Huck: Race, Identity, and the Teaching of Huckleberry Finn". Higher English. 57 (8): 919–937. doi:10.2307/378621. JSTOR 378621.

- ^ Twain, Marking (Samuel L. Clemens) (2001). The Annotated Blueberry Finn : Adventures of Blueberry Finn (Tom Sawyer'due south comrade). Introduction, notes, and bibliography past Michael Patrick Hearn (1st ed.). New York, NY [u.a.]: Norton. pp. xlv–xlvi. ISBN978-0-393-02039-7.

- ^ Cope, Virginia H. "Mark Twain'southward Blueberry Finn: Text, Illustrations, and Early on Reviews". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ Mark Twain and Michael Patrick Hearn, The Annotated Huckleberry Finn: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1981).

- ^ Philip Young, Ernest Hemingway: A Reconsideration, (University Park: Pennsylvania State Upwards, 1966), 212.

- ^ Baker, William (1996). "Reviewed work: Adventures of Blueberry Finn, Mark Twain". The Antioch Review. 54 (3): 363–364. doi:10.2307/4613362. hdl:2027/dul1.ark:/13960/t1sf9415m. JSTOR 4613362.

- ^ "Rita Reif, "First Half of 'Huck Finn,' in Twain's Mitt, Is Found," The New York Times, last modified Feb 17, 1991, accessed April 12, 2012".

- ^ William Baker, "Adventures of Blueberry Finn by Mark Twain"

- ^ McCrum, Robert (February 24, 2014). "The 100 best novels: No 23 – The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn past Mark Twain (1884/5)". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Walter Blair, Mark Twain & Huck Finn (Berkeley: University of California, 1960).

- ^ "All Modernistic Literature Comes from Ane Book by Mark Twain"

- ^ "Rita Reif, "ANTIQUES; How 'Huck Finn' Was Rescued," The New York Times, last modified March 17, 1991, accessed April 12, 2012".

- ^ Smith, Henry Nash; Finn, Huckleberry (1984). "The Publication of "Huckleberry Finn": A Centennial Retrospect". Message of the American University of Arts and Sciences. 37 (5): 18–40. doi:ten.2307/3823856. JSTOR 3823856.

- ^ "Norman Mailer, "Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100," The New York Times, terminal modified December ix, 1984, accessed April 12, 2012".

- ^ a b Leonard, James S.; Thomas A. Tenney; Thadious G. Davis (December 1992). Satire or Evasion?: Black Perspectives on Huckleberry Finn. Duke University Press. p. 2. ISBN978-0-8223-1174-4.

- ^ Shelley Fisher Fishkin, "Was Huck Blackness?: Mark Twain and African-American Voices" (New York: Oxford Upwardly, 1993) 115.

- ^ Brown, Robert. "One Hundred Years of Huck Finn". American Heritage Magazine. AmericanHeritage.com. Archived from the original on Jan 19, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

If Mr. Clemens cannot think of something amend to tell our pure-minded lads and lasses he had all-time terminate writing for them.

- ^ "One Hundred Years Of Huck Finn – AMERICAN HERITAGE". www.americanheritage.com.

- ^ "Marjorie Kehe, "The 'n'-word Gone from Huck Finn – What Would Marker Twain Say? A New Expurgated Edition of 'Huckleberry Finn' Has Got Some Twain Scholars up in Arms," The Christian Scientific discipline Monitor, last modified January v, 2011, accessed April 12, 2012".

- ^ "Nick Gillespie, "Mark Twain vs. Tom Sawyer: The Bold Deconstruction of a National Icon," Reason, last modified February 2006, accessed April 12, 2012".

- ^ Ernest Hemingway (1935). Green Hills of Africa . New York: Scribner. p. 22.

- ^ Norman Mailer, "Huckleberry Finn, Alive at 100"

- ^ "Twentieth Century Fiction and the Mask of Humanity" in Shadow and Deed

- ^ Ron Powers (2005). Marking Twain: A Life . New York: FreePress. pp. 476–77.

- ^ Mark Twain and Michael Patrick Hearn, eight.

- ^ For example, Shelley Fisher Fishin, Lighting out for the Territory: Reflections on Marking Twain and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- ^ "Stephen Railton, "Jim and Marker Twain: What Do Dey Stan' For?," The Virginia Quarterly Review, concluding modified 1987, accessed Apr 12, 2012".

- ^ Alex Sharp, "Student Edition of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer Is Censored past Editor"

- ^ Robert B. Brown, "1 Hundred Years of Huck Finn"

- ^ "100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999". March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Gregory Roberts, "'Huck Finn' a Masterpiece -- or an Insult," Seattle Mail service-Intelligencer, last modified November 25, 2003, accessed April 12, 2012".

- ^ "Wash. teacher calls for 'Huck Finn' ban". UPI. Jan 19, 2009.

- ^ "John Foley, "Guest Columnist: Time to Update Schools' Reading Lists," Seattle Mail-Intelligencer, terminal modified January 5, 2009, accessed April 13, 2012".

- ^ Allen, Nick (December 5, 2016). "To Kill a Mockingbird and Huckleberry Finn banned from schools in Virginia for racism". Telegraph . Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Books suspended by Va. school for racial slurs". CBS News. December ane, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ ""Huckleberry Finn" and the Due north-word fence". www.cbsnews.com . Retrieved August half-dozen, 2021.

- ^ "New Edition Of 'Huckleberry Finn' Will Eliminate Offensive Words". NPR.org. January iv, 2011.

- ^ "A word nearly the NewSouth edition of Mark Twain'southward Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn – NewSouth Books".

- ^ ""New Editions of Marking Twain Novels to Remove Racial Slurs," Herald Dominicus, last modified January 4, 2011, accessed April 16, 2012". Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved Jan iv, 2011.

- ^ Huck and Tom at the American Pic Institute Catalog

- ^ "IMDB, Huckleberry Finn (1920)".

- ^ a b wes-connors (Feb 29, 1920). "Huckleberry Finn (1920)". IMDb.

- ^ "IMDB, Blueberry Finn (1931)".

- ^ The Adventures of Blueberry Finn at the American Film Establish Itemize

- ^ The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at IMDb

- ^ The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ Hopelessly Lost at AllMovie

- ^ Huckleberry Finn at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ Huckleberry Finn at IMDb

- ^ The Adventures of Con Sawyer and Hucklemary Finn at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ The Adventures of Huck Finn at AllMovie

- ^ Tom and Huck at AllMovie

- ^ Love apple Sawyer and Blueberry Larry's Large River Rescue at IMDb

- ^ The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at IMDb

- ^ Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn at IMDb

- ^ Blueberry no Bōken (anime) at Anime News Network'due south encyclopedia

- ^ Huckleberry Finn and His Friends at IMDb

- ^ Blueberry Finn Monogatari (anime) at Anime News Network'south encyclopedia

- ^ The Adventures of Blueberry Finn in libraries (WorldCat itemize)

- ^ Large River at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Manga Classics: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (2017) UDON Entertainment ISBN 978-1772940176

- ^ Matthews, Greg (May 28, 1983). The Further Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Crown Publishers. ISBN9780517550571 – via Google Books.

- ^ "LeClair, Tom. "A Reconstruction and a Sequel." Sun Volume Review, The New York Times, September 25, 1983".

- ^ "Kirby, David. "Energetic Sequel to 'Huckleberry Finn' is Faithful to Original." The Christian Science Monitor, October 11, 1983".

- ^ "Kirkus Review: The Further Adventures of Blueberry Finn by Greg Matthews. Kirkus, September ix, 1983".

- ^ Ledin, Victor and Marina A. "GROFE: Grand Coulee Suite / Mississippi Suite / Niagara Falls". Naxos Records. Retrieved December viii, 2017.

- ^ "Huckleberry Finn EP". Duke Special. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at IMDb

Farther reading [edit]

- Beaver, Harold, et al., eds. "The Role of Structure in Tom Sawyer and Blueberry Finn." Blueberry Finn. Vol. 1. No. 8. (New York: Johns Hopkins Textual Studies, 1987) pp. 1–57.

- Brownish, Clarence A. "Huckleberry Finn: A Study in Construction and Point of View." Mark Twain Periodical 12.2 (1964): 10-15. Online

- Buchen, Callista. "Writing the Imperial Question at Home: Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer Amongst the Indians Revisited." Mark Twain Annual 9 (2011): 111-129. online

- Gribben, Alan. "Tom Sawyer, Tom Canty, and Blueberry Finn: The Boy Book and Mark Twain." Marking Twain Journal 55.ane/two (2017): 127-144 online

- Levy, Andrew, Huck Finn's America: Mark Twain and the Era that Shaped His Masterpiece. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015.

- Quirk, Tom. "The Flawed Greatness of Huckleberry Finn." American Literary Realism 45.1 (2012): 38-48.

- Saunders, George. "The United states of america of Huck: Introduction to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn." In Adventures of Blueberry Finn (Modernistic Library Classics, 2001) ISBN 978-0375757372, reprinted in Saunders, George, The Braindead Megaphone: Essays (New York: Riverhead Books, 2007) ISBN 978-1-59448-256-4

- Smiley, Jane (January 1996). "Say It Own't So, Huck: Second thoughts on Mark Twain's "masterpiece"" (PDF). Harper's Magazine. 292 (1748): 61–.

- Tibbetts, John C., And James Chiliad, Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2005) pp i–3.

Study and teaching tools [edit]

- "The Adventures of Blueberry Finn". SparkNotes. Archived from the original on September 19, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Study Guide and Lesson Plan". GradeSaver. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- "Huckleberry Finn". CliffsNotes. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- "Huck Finn in Context:A Education Guide". PBS.org. Archived from the original on September fourteen, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

External links [edit]

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at Standard Ebooks

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at Project Gutenberg

-

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Adventures of Blueberry Finn, with all the original illustrations – Free Online – Mark Twain Project (printed 2003 Academy of California Press, online 2009 MTPO) Rich editorial cloth accompanies text, including detailed historical notes, glossaries, maps, and documentary appendixes, which record the writer's revisions likewise as unauthorized textual variations.

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Digitized copy of the first American edition from Net Annal (1885).

- "Special Collections: Marker Twain Room (Houses original manuscript of Huckleberry Finn)". Libraries of Buffalo & Erie County. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adventures_of_Huckleberry_Finn

0 Response to "When Does Finn Find Out the Baby Is Not His"

Post a Comment